St. Joseph's Hospital and Health Center

125 Years of Service

Commendation from the Governor

Take a look at the State of Arizona Commendation sent to us by the Governor of Arizona, Douglas A. Ducey.

History of St. Joseph's

The 125 year history of St. Joseph's Hospital and Medical Center is rich and varied. Take some time to learn how our amazing community treasure came to be what it is today.

Throwback Thursdays

In honor of the anniversary, here are our special Throwback Thursday messages we are sending out each Thursday throughout 2020.

In January 1895, the Sisters of Mercy rented a six-room cottage on Polk and Fourth Streets in downtown Phoenix that became known as St. Joseph’s Sanitarium. Dedicated to the treatment of patients who suffered from tuberculosis, the sanitarium evolved to help others in need and eventually grew to become St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center.

While the Sisters of Mercy initially came to Phoenix to start a school, they were so moved by those suffering from tuberculosis that they began to care for patients in a six-room cottage at Polk and Fourth Streets. According to the sisters’ annuals: “These poor afflicted ones had come to Phoenix believing that a few months on the desert, breathing its dry air, would effect a cure. They were, however, unwelcome visitors. The doors of the hotels were closed to them. The poor health seekers were left to choose between a tent on the desert or a cot in a cheap boarding house. Many died alone and were buried— nameless—in paupers’ graves.

In an effort to help these individuals, the Sisters of Mercy opened what became known as St. Joseph’s Sanitarium. Even then, the TB patients faced disdain. Believing their work was devaluing his property, the landlord of the cottage began legal proceedings to evict the sisters and their patients. Still, the sisters persisted in their care of the less fortunate, and the sanitarium evolved into St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center. One-hundred-and-twenty-five years later, that important work continues today.

Fun Fact: Many of Phoenix’s institutions and landmarks were started to care for tuberculosis patients or by those with the disease. These include: Bethany Home Road, Phoenix Mystery Castle, Desert Mission, and Helen Lincoln (wife of John C. Lincoln, for whom the hospital and Lincoln Road are named).

Shortly after the Sisters of Mercy began caring for tuberculosis patients in a six-room cottage at Polk and Fourth Streets, the property’s landlord started legal proceedings to evict them. He believed the Sisters’ work was devaluing his property.

Other citizens recognized the importance of the Sisters’ efforts. Friends in the business community helped the women religious purchase the small cottage, and Gen. Clark Churchill donated two adjoining lots.

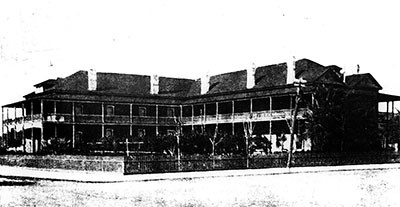

The donation and generous contributions allowed the Sisters to break ground on a “real” hospital on March 19, 1895, the Feast of St. Joseph’s. The new two-story St. Joseph’s Hospital opened in fall of that year. It featured 24 private rooms and sweeping porches. The common cost for a week’s visit was $10.

Fun Fact: Over the years, St. Joseph’s has provided care in several buildings, but its main campus has only ever occupied two sites: Polk and Fourth Streets and its current address at 350 W. Thomas Road. Ironically, the Dignity Health – Cancer Institute at St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center opened a few short blocks from where the original hospital was located.

Throughout the hospital’s 125-year history, St. Joseph’s and the Sisters of Mercy faced several different kinds of adversity—including the weather. Air conditioning was not widely adopted in Phoenix until after World War II. Prior to that, some physicians wore two pairs of boots during surgery. One pair was much larger than the other, and physicians would fill the gap between the two with ice to keep cool. The Sisters also used ice to cool patient rooms, setting up fans over big ice blocks to create a pleasant breeze and provide comfort. In the hospital kitchen, Sister Mary Agnes tended to “St. Agnes’ Well,” a big jug of ice water that was available 24 hours a day.

The Sisters likely needed more water than most. For many years, they wore wool habits and heavy fabrics that trailed to their ankles. Sister Alice Montgomery recalled it getting so hot that starch would “melt” and run down her face. When a visitor witnessed the spectacle and asked what was happening, she replied she was having “a little meltdown.”

Of course, heat isn’t the only harsh weather the hospital has endured. St. Joseph’s has also experienced its share of thunderstorms, dealt with flooding and wind damage, and even been covered in snow. Above is a picture of two Sisters and a physician standing on the hospital roof, shortly after an inch of snow fell in January 1937.

Fun Fact: The Sisters were not the only ones to use creative methods to keep cool during Phoenix’s hottest months. Many people slept on roofs, in yards, or on porches during the summer. It wasn’t unheard of for people to wrap themselves in wet sheets. Some individuals who slept outside put the legs of their iron cots into cans of water to ward off scorpions and insects.

The 2019 Novel Coronavirus has been heavily covered by international media but in 1918, another disease was the focus of headlines from around the world: A strain of influenza spread globally and would eventually become a pandemic, impacting an estimated 500 million people.

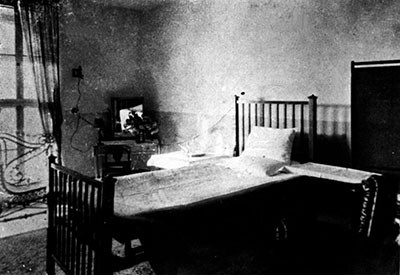

To accommodate flu patients filling St. Joseph’s Hospital, two rows of beds were placed in the hospital’s long ward. Portable screens separated the men’s and women’s section. As the number of patients grew, St. Joseph’s ran out of patient beds, so treatment areas were set up in the hospital’s corridors. The Women’s Club and other buildings throughout the city became “emergency hospitals.” When a bed opened, St. Joseph’s would receive a transfer from the emergency facilities.

The Valley’s population of doctors and nurses had already been stretched by World War I, so volunteers helped tend to the sick. Despite Prohibition, the Maricopa County Sheriff’s Office sent St. Joseph’s a supply of “spirits,” to be administered to patients.

In Arizona, schools, theaters, and other public areas were closed for as long as three months. In Phoenix, dogs were killed and residents who ventured out without a gauze mask were arrested, under the false belief that both would help stop the spread of the disease.

By October, the epidemic made its way through much of the city, but other areas of the state were still overwhelmed.

St. Joseph’s Sisters were asked to help the mining town of Globe. All the Sisters volunteered for duty, and four were appointed to tend to the sick. The residents were very grateful for the help and had the Gila County Sheriff present the Sisters with a check on behalf of the citizens.

Fun Fact: Former Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater’s mother, a nurse who had “retired” to raise a family, volunteered at St. Joseph’s during the pandemic and worked around the clock with the Sisters and other volunteers to care for the sick.

On February 14, 2020, Arizona celebrated 108 years of statehood. When the Sisters of Mercy opened St. Joseph’s in 1895, Arizona was still a territory and much less populated. According to the census, Arizona had 122,931 residents in 1890.

Despite Arizona’s size and formidable terrain, the Sisters’ work took them all over the territory and beyond. When the hospital was in need of funds, the Sisters would take “collection” trips, traveling to Tombstone, Bisbee, Douglas, Nogales, and Tucson.

In some communities, the women religious would descend into mines or wait outside of banks on paydays, hoping that friendly miners would give to their cause. The Sisters were often met with generosity and donations in increments of fifty cents. A grocer in Bisbee once told a Sister that she could have all the groceries she cared to accept, but that he would not give her money. He then handed her $25.

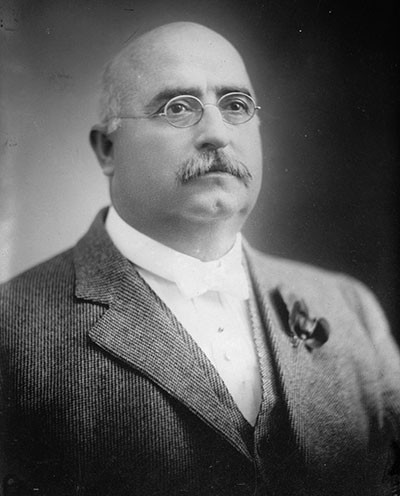

St. Joseph’s has been the site of many special events over the years, even serving as the “state capitol” for a short time in 1924. In that year, Arizona Governor George W.P. Hunt underwent surgery at St. Joseph’s for appendicitis.

Governor Hunt’s surgery went so well that he was soon allowed to transact business from his hospital bed. This was during the pre-election period, and the Sisters of Mercy noted that the work of the governor and his secretaries increased daily. Governor Hunt was discharged from the hospital after a smooth recovery, generously leaving St. Joseph’s chapel full of flowers that had been sent to him.

Governor Hunt would return to St. Joseph’s in 1932 while suffering from a long illness. During his hospitalization, the governor affixed his signature to a petition presented by the residents of the State of Arizona. The petition focused on offsetting the restrictions imposed by the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution (the petition mainly focused on ending Prohibition).

Fun Fact: George W.P. Hunt was Arizona’s first governor, who served seven terms between February 1912 and January 1933. He referred to himself as “Old Walrus.” Governor Hunt was a Freemason and, inspired by the pyramids of Egypt, built a tomb for his wife after she died in 1931. Many Phoenix residents are familiar with Hunt’s Tomb, which is the white pyramid in the heart of Papago Park and visible from the Phoenix Zoo. Governor Hunt was also interred there after he died of heart failure on Christmas Eve in 1934.

By early 1942, Arizonans were feeling the effects of the United States’ involvement in World War II. The Sisters noted that while Arizona had no shoreline, the Lord had provided the state with some water and plenty of sand—just what authorities had ordered in case of air raids. St. Joseph’s roof was equipped with both items, along with shovels, should a raid result in fire.

The Red Cross established a plasma bank in St. Joseph’s laboratory, and Red Cross nursing aides trained three hours a day at the hospital. The extra help came in handy as the Sisters witnessed their doctors and nurses leave for military service almost on a weekly basis. According to the hospital’s annuals, Dr. E.P. Palmer felt “lost” without the assistance of his two physician sons, Payne and Paul, who had been called to military duty.

When the Arizona Hospital Association convened in late February 1942, they discussed the challenges associated with the national defense in terms of nursing staff, supplies, equipment, personnel, laundry, and more. Like many hospitals, St. Joseph’s experienced acute staffing shortages with so many personnel working in the military and local war industries.

Later that year, the Sisters shared that the hospital’s emergency department team got a sense of what their colleagues were experiencing on the military fields. According to the hospital’s annuals, military police had broken up a local fight, during which a machine gun had been fired into the crowd. Three were killed and many of the 18 injured came to St. Joseph’s.

Fun Fact: Hollywood star Joan Fontaine volunteered at St. Joseph’s during World War II as an aide for the Red Cross. Joan’s husband, actor Brian Ahearne, served at one of the local military camps. Although not Catholic, the starlet had requested to work at a Catholic hospital. St. Joseph’s nurses were surprised when the movie star bathed four patients one morning and was then ready for more work.

Throughout its history, St. Joseph’s Hospital and Medical Center has been blessed by the generosity of others. One early benefactor was Mr. Daniel O’Carroll who, in the spring of 1906, surprised the Sisters of Mercy with a check for $500.

Mr. O’Carroll emigrated from Ireland when he was a boy and spent most of his life mining the Arizona mountains for gold. By 1912, the miner and Civil War veteran’s interest in the hospital had increased, and he often stayed at St. Joseph’s as a guest. During one visit, he decided that the family living next door did not make suitable neighbors for the Sisters, so he bought the neighboring cottage and then donated it to the hospital. A few months later, he did the same with another cottage. Both buildings were used to house nurses.

Mr. O’Carroll’s generosity was not limited to the hospital. In 1915, he asked the Sisters to care for a patient at a local tubercular sanitarium. The Sisters took in the young lady, who lived at St. Joseph’s until her death in 1923. When Mr. O’Carroll learned that another patient, a boy named William Murphy, wanted to return to Ireland to die, Mr. O’Carroll immediately furnished the means to take him home.

During fundraising efforts in 1917, Mr. O’Carroll donated an additional $5,000 to St. Joseph’s. Upon his death, Mr. O’Carroll left two-thirds of his estate to the hospital.

Admiring the Sisters and their work, his first donation was made to defray the expense of painting and decorating the hospital halls and patient rooms.

Fun Facts: When reading the Sisters’ annuals, the history of Mr. O’Carroll takes on some of the folkloric qualities found in other stories about early miners. In 1906, Mr. O’Carroll, a satisfied patient, is described as being a gentleman more than 90 years old who insisted that he was of hearty health except “for a little stiffness of the limbs.” In 1915, it’s noted that Mr. O’Carroll, who loved all things Catholic, considered himself an “outsider” who had not been to church since he was a boy. Having drifted from religious influences in his later years, he lived a hermit’s life with his dog and two burros while prospecting for gold in Arizona. The Sisters often prayed for Mr. O’Carroll’s reconciliation with the Catholic Church and that was achieved when he was hospitalized at St. Joseph’s for a time in 1924. When Mr. O’Carroll died four years later, at the reported age of 113, he remarked that God had taken good care of him.